There and Back Again Cai Guo Chiang

Weaving motifs from Chinese culture, history, and thought, Cai Guo-Qiang began creating gunpowder drawings while living in Japan. What does the country mean for this world-leading contemporary creative person?

A Leading Contemporary Artist

Cai Guo-Qiang has used gunpowder and fireworks to explore new frontiers in art since his youth. After launching and developing his career as an artist in Nippon, he began presenting his works internationally and has held a large number of exhibitions worldwide.

Mermaid project for the 2010 Aichi Triennale. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Mermaid project for the 2010 Aichi Triennale. © Cai Guo-Qiang

In summer 2022 Cai—who past then had go one of the world'due south leading figures in gimmicky art—gave a big-scale solo exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art. Titled Cai Guo-Qiang: here and Back Again, the exhibition—held from July 11 to Oct 18—presented works embodying Cai's resolve to render to the country where he spent his formative years as an artist, get back in touch with Eastern and Japanese civilisation, and recall that essence in himself.

From Japan to the World

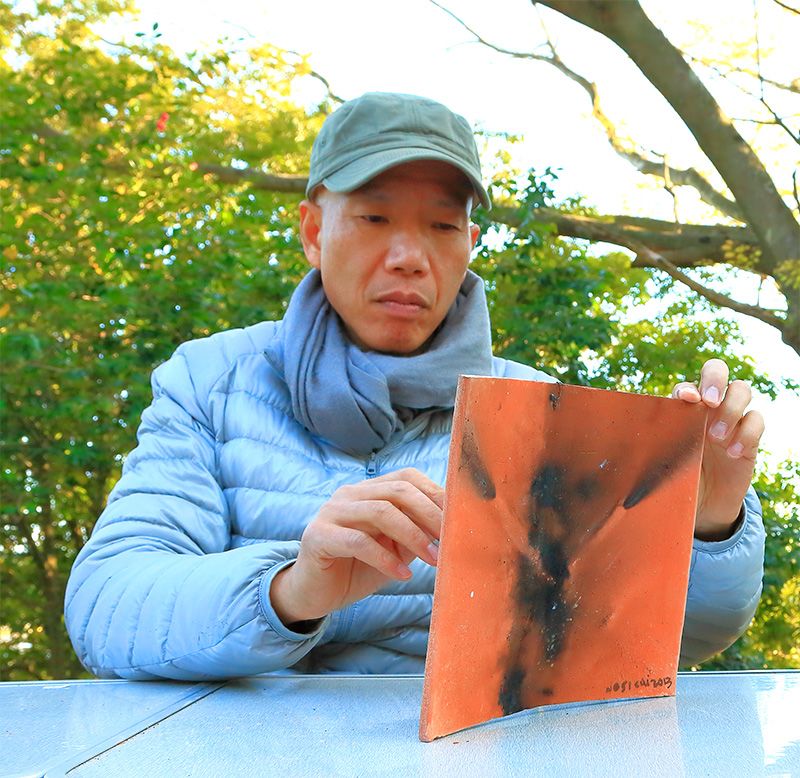

Cai signs a work created during Editions for SMoCA, ane of the opening events for the Snake Museum of Contemporary Art in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, in 2013. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Cai signs a work created during Editions for SMoCA, ane of the opening events for the Snake Museum of Contemporary Art in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, in 2013. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Born in 1957 in Quanzhou, Fujian Province, Cai Guo-Qiang came to Japan in 1986 after studying stage pattern at the Shanghai Theater University. He launched his artistic career while living in Tokyo, Toride, and Iwaki, and too studied at the University of Tsukuba. While in Nippon Cai began making drawings using gunpowder on washi (Japanese paper). He conducted a serial of big-calibration outdoor explosive events called Project for Extraterrestrials at various venues, including equally part of the 1991 Exceptional Passage: Chinese Avant-Garde Artists Exhibition in Fukuoka and other group exhibitions.

Afterward moving to New York in 1995, Cai has continued to work in various locations, from the Americas and Europe to Australia, and has won numerous prizes, including the Golden Lion at the 1999 Venice Biennale. He was artistic director of the closing ceremonies of the 2001 APEC Conference and managing director of visual and special effects for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing—wowing telly viewers around the world with spectacular fireworks displays.

Contemporary and Traditional Motifs

While constantly experimenting with new techniques, Cai also incorporates elements of traditional Chinese culture, such as feng shui philosophy and Chinese medicine, perhaps reflecting his determination not to get swept up in the latest trends in Western contemporary fine art. At that place is an unfettered feeling about his art that, combined with the artist's easygoing demeanor, instantly draw viewers into his works.

The catalogue of the There and Back Again exhibition contains an autobiographical essay, "The 99 Stories of Cai Guo-Qiang." In it Cai tells tales far removed from contemporary fine art: his memories of Quanzhou, where feng shui is nevertheless a living philosophy; the dear he received from his grandparents and parents; near shaman ladies, ghosts, and hermits; and dream divination at a Taoist temple, among others. These stories offer intriguing clues to understanding Cai's works. (The number 99 signifies an infinite bike in Taoist thought.)

Mermaid, a drawing for the 2010 Aichi Triennale. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Mermaid, a drawing for the 2010 Aichi Triennale. © Cai Guo-Qiang

At that place—and Back Again

Even after moving to New York, Cai would return to Nippon every two or iii years for exhibitions and symposiums. He has been dorsum every twelvemonth since the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, opening the Snake Museum of Contemporary Art in 2013 equally role of the Iwaki Manbon Sakura Projection that he launched with the people of Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. The goal of the project, which is being conducted with Cai's support, is to constitute 99,000 cherry trees over the grade of 99 years; more than 2,000 trees accept already been planted.

Ignition of Editions for SMoCA (Snake Museum of Gimmicky Art), an opening consequence for the museum in Iwaki. © Cai Guo-Qiang.

Ignition of Editions for SMoCA (Snake Museum of Gimmicky Art), an opening consequence for the museum in Iwaki. © Cai Guo-Qiang.

Only as he was contemplating increasing his activities in Nihon, Cai was invited by the Yokohama Museum of Fine art to do a solo exhibition.

The championship of the exhibition—At that place and Dorsum Again—derives from "Gui qu lai ci" (The Return), a famous verse form by Tao Yuanming describing nostalgia for his hometown. It signifies Cai's return to his artistic "home" and his hope of recapturing the innocence he had every bit a immature artist past retracing his roots. Also included in the exhibition catalogue is an essay well-nigh his thoughts on his latest render to Nippon. He writes, "I focused on pictorial art, thinking most limerick and emotive elements in Japanese paintings and besides near Eastern civilisation, philosophy, and ways of life. These I sought to translate into the linguistic communication and expressive techniques of contemporary visual art."

Cai besides notes that, as he researched the life and writings of Okakura Kakuzō, his interest expanded from performance art to visual art. Okakura was instrumental in establishing the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, founded the Nippon Bijutsuin (Japan Fine art Institute), and later headed the Asian art division of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Fifty-fifty as the wave of Westernization swept through Meiji-era (1868–1912) Nippon, Okakura was intensely enlightened of Eastern values and their global relevance. In the hope of conveying their essence to the Western world, he wrote The Book of Tea (1906) in English.

Daytime Fireworks

When Cai lived in Nippon, he experimented extensively with fireworks made for daytime utilize to limited color. He used colored fireworks in such recent events as Blackness Rainbow in Spain (2005) and Blackness Fireworks in Hiroshima (2008) and fabricated slap-up technical strides in daytime fireworks for the opening of his 2022 solo exhibition in Shanghai, Cai Guo-Qiang: The Ninth Wave.

Black Fireworks, a 60-2d effect using black smoke shells, held on October 25, 2008, at Motomachi Riverside Park near the Diminutive Bomb Dome in Hiroshima; deputed by the Hiroshima City Museum of Gimmicky Art. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Black Fireworks, a 60-2d effect using black smoke shells, held on October 25, 2008, at Motomachi Riverside Park near the Diminutive Bomb Dome in Hiroshima; deputed by the Hiroshima City Museum of Gimmicky Art. © Cai Guo-Qiang

Whereas nighttime fireworks use low-cal as the expressive medium and fade instantly, daytime fireworks primarily employ fume. The smoke drifts with the wind, haemorrhage and melting into the canvas of the sky like an ink or watercolor painting. The sense of color and emotion that Cai developed through his work with daytime fireworks led to the Seasons of Life series, his first foray into shunga (erotic art), which he created for the Yokohama exhibition.

Seasons of Life: Summertime, 2015. Gunpowder on canvas. 259 cm ten 648 cm. From the artist'due south collection. Photo courtesy of the Yokohama Museum of Fine art.

Seasons of Life: Summertime, 2015. Gunpowder on canvas. 259 cm ten 648 cm. From the artist'due south collection. Photo courtesy of the Yokohama Museum of Fine art.

Seasons of Life: Bound, 2015. Gunpowder on sheet. 259 cm x 648 cm. From the artist's drove; displayed at Ignition, the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photograph by Kamiyama Yōsuke.

Seasons of Life: Bound, 2015. Gunpowder on sheet. 259 cm x 648 cm. From the artist's drove; displayed at Ignition, the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photograph by Kamiyama Yōsuke.

Shunga is an expression of the menstruation of life and incorporates seasonal changes in nature. This is truthful to the Eastern concept of unity of fourth dimension and space, a concept that likewise extends to contemporary art. The medium of fireworks, which defies full homo control, can lead to expressions of beauty even beyond the creative person'south imagination. As Okakura wrote, the essence of Japanese culture lies in delicate attempts to notice eternal beauty in the imperfect.

A New Journeying

One of the most impressive works at the Yokohama exhibition was Nighttime Sakura, an 8-meter high, 24-meter wide work that Cai produced in Nippon using washi and that was displayed in the museum's Grand Gallery. Information technology depicts cherry blossoms spreading their tender petals, along with an owl, hidden among the blossoms, staring down at viewers with a piercing gaze.

Nighttime Sakura, 2015. Gunpowder on newspaper. 800 cm ten 2,400 cm. From the artist'south drove; viewed in installation at the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photo by Gu Kenryou. © Cai Studio

Nighttime Sakura, 2015. Gunpowder on newspaper. 800 cm ten 2,400 cm. From the artist'south drove; viewed in installation at the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photo by Gu Kenryou. © Cai Studio

Dark Sakura, 2015. Gunpowder on paper. 800 cm x ii,400 cm. From the artist's collection; displayed at Ignition, the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photo by Cai Wen-You. © Cai Studio

Dark Sakura, 2015. Gunpowder on paper. 800 cm x ii,400 cm. From the artist's collection; displayed at Ignition, the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2015. Photo by Cai Wen-You. © Cai Studio

As with Seasons of Life, this piece of work was made without the use of paintbrushes—but gunpowder ignited on paper. Asked in a tv set interview why he chose to depict sakura, Cai replied, "The life of cerise blossoms is fleeting; they're gone in no time. And nonetheless we wait all year for spring to come. At that place is something about the power and beauty of the blossoms that resonate with gunpowder."

His near recent visit to Nippon, Cai says, was an attempt to recapture the "East" within him as the culmination of a journeying that has brought him many things. The world eagerly awaits the adjacent leg of Cai Guo-Qiang's remarkable creative journey.

(Originally written in Japanese past Demura Kōichi and published on July 22, 2016. Photographs past Izumiya Gensaku, unless otherwise noted. Banner photograph: Transient Rainbow, a fifteen-second issue over the East River in New York, held on June 29, 2002, using 1,000 three-inch multicolor peony fireworks fitted with computer fries; commissioned by the Museum of Modern Fine art, New York, for the opening of MoMA Queens.)

Source: https://www.nippon.com/en/views/b02310/

Post a Comment for "There and Back Again Cai Guo Chiang"